John Deere strike: What to know

United Auto Workers at John Deere plants in several states walked off the job at midnight Oct. 14

Food prices will go up ‘tremendously’: John Catsimatidis

Gristedes and D'agostino Foods President and United Refining Company CEO John Catsimatidis weighs in on the increase of food prices in the U.S.

It's been nearly a week since more than 10,000 United Auto Workers members walked off the job at John Deere plants in several states after rejecting the agriculture equipment giant's latest contract offer.

As Deere & Co. employees at 14 facilities spanning Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa and Kansas take part in the company's first strike in 35 years, both parties have remained relatively mum on details so far throughout the ongoing strike and negotiations.

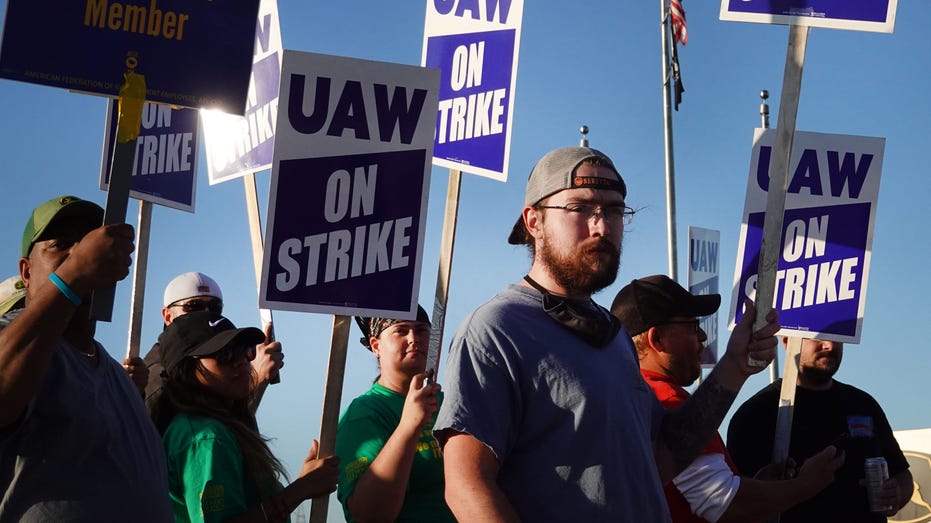

Striking workers picket outside of the John Deere Davenport Works facility Oct. 15, 2021 in Davenport, Iowa. More than 10,000 John Deere employees, represented by the UAW, walked off the job after failing to agree to the terms of a new contract. (Sco (Scott Olson / Getty Images)

In the meantime, FOX Business gives a breakdown of what to know about the situation.

John Deere's position

Deere & Co. provides what it argues is a robust compensation and benefits package already and pushed a deal across the table that would have meant 5% raises for some workers and 6% raises for others, with 3% raises in 2023 and 2025.

The company says that under the tentative agreement, the typical John Deere worker's annual pay would have gone from $60,000 to nearly $72,000, and employees would still have continued to pay nothing in health insurance deductibles or premiums despite health care costs expecting to rise from $12 to $17 per hour for the company. John Deere also offered to boost retirement bonuses.

A worker performs maintenance on a Deere & Co. John Deere combine harvester at the Smith Implements Inc. dealership in Greensburg, Ind. (Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg )

HOW LONG WILL THE LABOR SHORTAGE LAST?

The company admitted earlier this year that it was having trouble filling positions just like other businesses across the U.S. and is now relying on trained non-union workers to keep things running at impacted plants during the strike.

"Beyond reaching a mutually beneficial agreement with the UAW, Deere’s immediate concern is meeting the needs of our customers who work in time-sensitive and critical industries such as agriculture and construction – i.e. many U.S. farmers are currently harvesting," John Deere spokeswoman Jennifer Hartmann told FOX Business. "For that reason, we’re committed to keeping our operations, including our parts distribution center and parts depots, up and running."

Hartmann added, "Our intention is to protect the livelihoods of all those who rely upon us, including our employees, dealers, suppliers and communities."

UAW's position

Striking Deere workers are pointing to the company's record profits and argue that their dedication and hard work throughout the COVID-19 pandemic should earn them more than what their employer brought to the table last week. Roughly 90% of the UAW workers rejected the tentative deal.

"Strikes are never easy on workers or their families, but John Deere workers believe they deserve a better share of the pie, a safer workplace and adequate benefits," UAW Region 8 Director Mitchell Smith said in a statement at the beginning of the strike.

Workers picket outside a John Deere Harvester Works plant on Oct. 14, 2021 in East Moline, Illinois. More than 10,000 Deere employees represented by the UAW walked off the job after failing to agree to terms of a new contract. (Scott Olson/Getty Images / Getty Images)

RETAILERS FORECAST DISAPPOINTING HOLIDAY SEASON AS LABOR SHORTAGE RAGES

The Deere employees have a great degree of leverage given America's labor shortage, which has caused some small businesses to close. One worker told The Des Moines Register that now is the time to hold the line against their employer, which is an international powerhouse.

"The whole nation's going to be watching us," Deere painter Chris Laursen told the outlet last week. "If we take a stand here for ourselves, our families, for basic human prosperity, it’s going to make a difference for the whole manufacturing industry. Let’s do it. Let’s not be intimidated."

The union is paying striking Deere workers $275 per week until a resolution is reached between workers and the company. In the meantime, workers are picketing around the clock.

The impact beyond Deere and striking workers

Concerns are growing over how the strike's impact could extend beyond just Deere and its UAW members.

In addition to the massive labor shortage and supply chain crisis in the U.S., the strike means additional pressures during harvest season when farmers need to remain operational.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

Food prices will eventually be impacted by the strike, too, as producers are hit with a double whammy of shortages and increased input costs that will hit consumers in the pocketbook down the line.

The Associated Press contributed to this report